SHARES

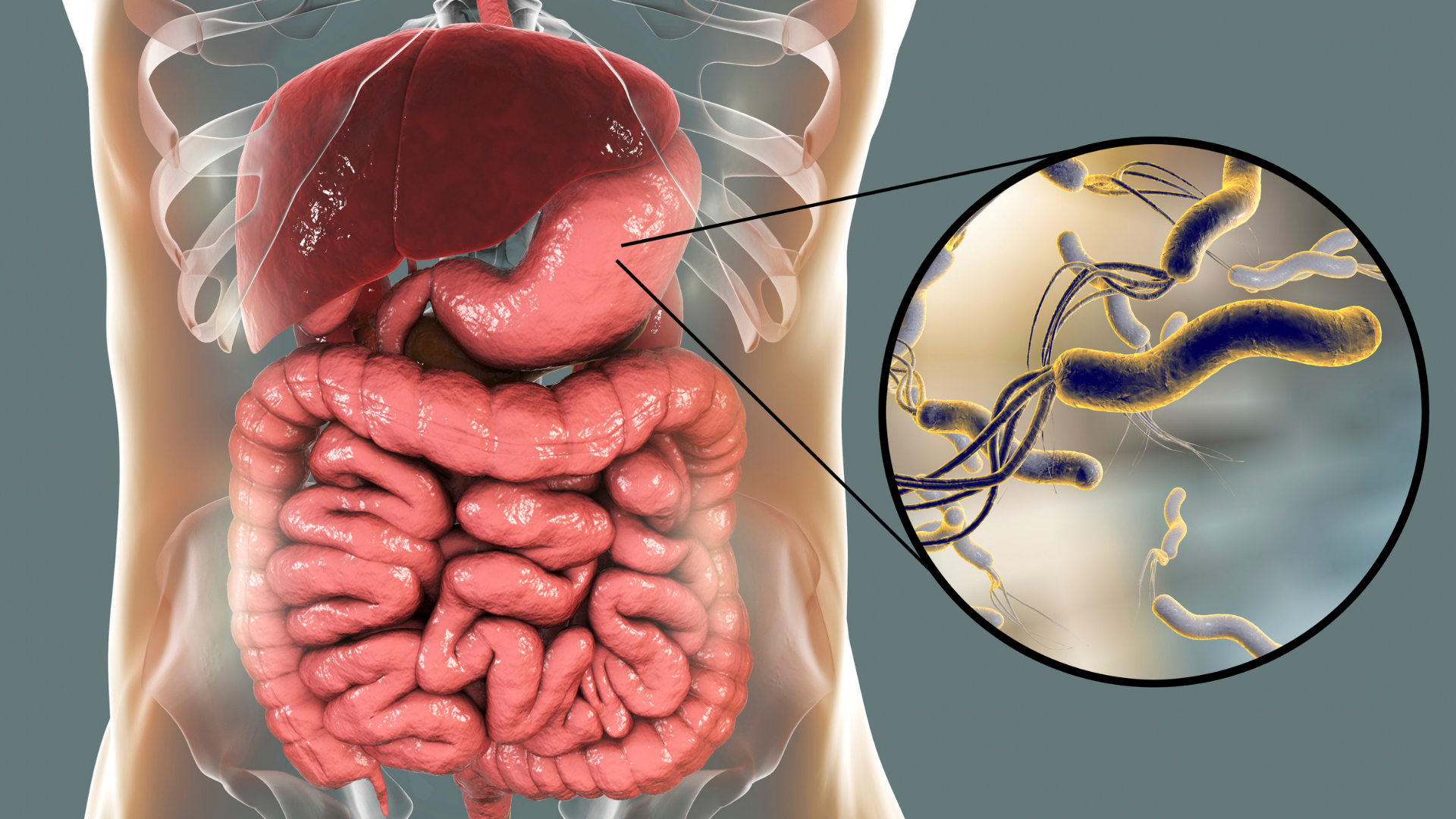

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria has a spiral shape, commonly present in the human stomach and small intestines. It was estimated that half of the world’s population may have a chronic infection with H. pylori. Apparently, it is especially prevalent in poor developing countries.

Interestingly, the discovery of H. pylori in man has been relatively recent. An Australian pathologist, Dr Robin Warren, first described it in 1981. He noticed a corkscrew-looking microorganism in the biopsy specimens of patients with stomach ulcers and cancers. Together with Dr Barry Marshall, then a young physician in training, they made the significant observation. H. pylori causes an inflammation of the stomach called gastritis. This in turn led to the erosion of the stomach lining or ulcers.

Prior to this, doctors had widely believed that stomach and duodenal ulcers were due to excessive acid in the stomach, due to stress, cigarette smoking or irregular meals. In fact, classic surgical textbooks had described operations to cure ulcers by removing the part of the stomach that produces acid or by cutting the nerves that control the secretion of acid in the stomach. By the 1980s, drug companies were treating ulcers with acid blockers such as Zantac (ranitidine) and Tagamet (cimetidine). However, despite allowing the ulcers to heal, the condition usually recurs when the patients stop taking the drugs.

It took Dr Marshall and Dr Warren many scientific presentations and publications before they could convince other doctors that the bacterium is the cause of ulcers. In fact, Dr Marshall inoculated himself with H. pylori to show that it causes gastritis in a healthy male volunteer (himself). This brave experiment, and many more clinical trials that followed, eventually convinced the world. Antibiotics that eradicate H. pylori can cure ulcers! In recognition to their contribution, Dr Marshall and Dr Warren were awarded with the Nobel Price in 2005.

Helicobacter Pylori Transmission

We now know that H. pylori can also exist as a commensal in some people’s stomach without causing any symptoms or disease. We cannot exactly predict whether H. pylori can cause problems in you as there may be multiple undefined host and bacterial virulence factors. In other words, some strains of H. pylori may be more aggressive in causing problems in humans. And some people may be more susceptible to developing these problems compared to others.

Besides staying in the stomach, H. pylori can also be present in our saliva and faeces. As such, the usual route of H. pylori infection is either oral-to-oral or faecal-to-oral contact. Infections occur in most people in their childhood, especially from contaminated food and water sources. We may also get it by sharing food with infected people. This may be a reason why H. pylori is especially common in Asia where eating from communal dishes is part and parcel of life.

Testing for Helicobacter Pylori

H. pylori infection can cause symptoms such as bloating, indigestion, vomiting, upper abdominal discomfort, halitosis (bad breath) and diarrhoea. Your doctor may order a test for H. pylori if he/she suspects that this is the cause of your symptoms.

If you have a history of ulcers, the testing for H. pylori is useful too. This is also the case, if you are require other long-term medication that can increase the risk of bleeding from ulcers. These drugs include aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen.

H. pylori is frequently present in the stomach of patients with stomach cancer. In fact, HP was classified as a Class I carcinogen for stomach cancer by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994. If you are at high risk for stomach cancer (e.g. if there is a history of stomach cancer in your immediate family), we may recommend testing for and treating H. pylori to reduce your future risk of developing this cancer.

Helicobacter Pylori Tests

Testing for H. pylori is relatively easy and accurate. You can take a non-invasive urea breath test (UBT) or a faecal antigen test.

The UBT is a simple, safe and non-invasive test developed by Dr Marshall, based on the ability of HP to break down urea to form ammonia. It is very accurate, with 95% sensitivity and specificity.

To do this test, come to the clinic in the morning after fasting for at least 6 hours (no food or water to be consumed). Do not smoke for 6 hours before the test. And avoid taking antibiotics for 1 month before the test date, as well as gastric medication for 1 week before the test date. This is because these drugs may interfere with the accuracy of the test results.

You will be asked to swallow a tablet containing 100mg of urea labelled with a 13C isotope tracer (this substance is not radioactive). If H. pylori is present in your stomach, the urea will be degraded into carbon dioxide and ammonia. The carbon dioxide is absorbed by the stomach, passes into the blood and travels to the lungs where it is excreted in the breath. The 13C labelled carbon dioxide can be detected in the laboratory by collecting the exhaled breath in a bag 20 minutes after swallowing the urea tablet.

A blood test for H. pylori is also available for serology testing of H. pylori antibodies. However we do not recommend this test as a positive test cannot differentiate between current active infections and a past one, as H. pylori antibodies may persist for many years after eradication.

Gastroscopy

We can also test for H. pylori by doing a gastroscopy. During gastroscopy, we take a stomach lining biopsy. The biopsy tissue is examined for H. pylori under a microscope, or put it into a rapid urease test kit. If H. pylori is present, it converts urea in the test kit to ammonia. Because of a change in pH, the indication is visual colour change in the test kit. In cases of H. pylori with antibiotic resistance, we can also obtain a specimen from the stomach to culture the bacteria in the laboratory. Once the organism has been cultured, we can test its sensitivity to various antibiotics to guide further treatment.

Gastroscopy is the gold standard of testing for H. pylori, as it also gives a very accurate visual assessment of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. It is an important diagnostic tool for patients who has complaints of “gastritis” and other digestive symptoms.

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Gastritis

To the layman, “gastritis” is often used to denote symptoms of indigestion, bloating, discomfort or even pain in the upper abdomen. However, to doctors, gastritis is a specific diagnosis of inflammation in the inner lining of the stomach. Besides H. pylori, gastritis can also be caused by excessive acid in the stomach, drugs, alcohol and smoking.

A diagnosis of gastritis is usually made by gastroscopy. A normal stomach has healthy pinkish lining and small folds. Instead, gastritis can appear as a colour change, or as nodularity, erosions or irregularities. We will usually take a biopsy from the stomach to look under the microscope. The pathologist will come out with the final diagnosis in a few days.

Besides gastritis, the gastroscopy examination can also detect other problems in the stomach, such as ulcers and cancers. We are now able to detect cancers and pre-cancers at a very early stage by using optical enhancements during endoscopy, such as magnification and chromoendoscopy.

Stomach cancer is curable if it’s detection is in the early stages. Identification of pre-cancer changes in the stomach, such as intestinal metaplasia, can also help stratify high risk groups for surveillance. A H. pylori test and eradication treatment can reduce the incidence of gastric cancer.

Treatment of Helicobacter Pylori

Doctors prescribe treatment only for patients with a positive test result for H. pylori. Selecting the right treatment can be challenging. The regime is to take a combination of three or four medications (antibiotics, acid blockers and probiotics) multiple times a day for 10 to 14 days. The success rate of eradicating H. pylori completely is about 80%, due to increasing antibiotic resistance worldwide. As such, the recommendation is to to have a UBT 1 to 3 months after treatment to confirm successful eradication. In persistent H. pylori, a second or even third course of different antibiotics is sometimes required despite the completion of first line therapy. Fortunately, once H. pylori is successfully treated, the risk of a re-infection in the future is very low.

Special thanks to:

Dr Melvin Look is the Director of PanAsia Surgery in Mount Elizabeth Hospital, Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital and Parkway East Hospital. He is a Consultant Surgeon in Gastrointestinal, Laparoscopic and Obesity Surgery. In addition, he has a special interest in Endoscopy and the treatment of Digestive Diseases. He underwent various training awards at several hospitals. These include the National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh UK, Mount Sinai Medical Centre New York, and Washington Cancer Institute in Washington DC.

Disclaimer

Important: The team at GetDocSays have made extensive and reasonable efforts to ensure that medical information is accurate. They further ensure that the content conforms to the standards of the publication. However, they reflect the opinions and views of the contributors and not the publisher.

The information on this site is not professional advice nor to replace personal consultation with a health care professional. The reader should not disregard medical advice or delay seeking it because of information published here.

by Joanne Lee

Multipotentialite. Loves creating and seeing ideas come alive. View all articles by Joanne Lee.